Memorializing the “Splendid Little War” in Port Chester

By Patrick Raftery, from the Summer 2017 issue (Volume 93, Number 2) of The Westchester Historian.

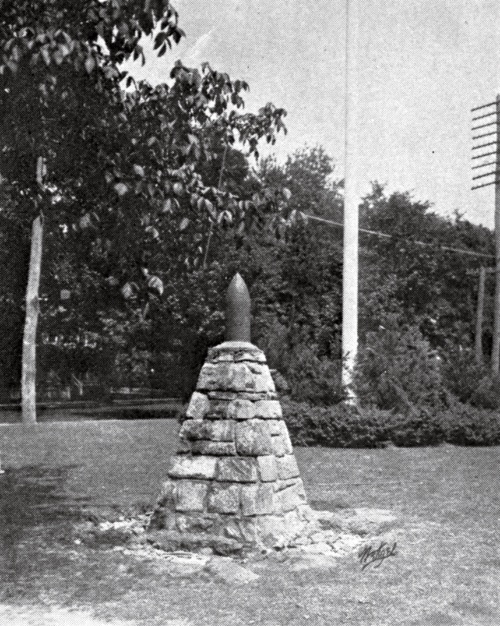

Each day hundreds of motorists driving out of downtown Port Chester on Willett Avenue sit at a traffic light at that street’s five-corner intersection with King and North Pearl streets. If a driver’s attention is attracted by anything at all while waiting for the red light to turn green, it is probably the large steeple of the former Summerfield United Methodist Church (now Antioch Christian Church). However, if the driver turns his or her head to the left toward tiny Summerfield Park, he or she will notice a monument consisting of a large artillery shell sitting atop a granite pillar. Behind this small monument stands a larger granite base topped by an unusual statue of a soldier. Its surface now patinated by time, this bronze figure looks quite different from the typical soldier that stands atop war memorials in Westchester County.

The history behind the memorials in Summerfield Park features several fascinating stories, including the only sailor from Westchester County to lose his life in the explosion of the USS Maine; another of the first Spanish-American War veterans’ organizations in the United States; a third of a Westchester artist who served his country in three armed conflicts yet used his sculpture to draw attention to the horrors of war; and, finally, a spirited community debate about the purpose of war memorials.

The Loss of the USS Maine

At 9:40 pm on February 15, 1898, an explosion sank the USS Maine in the harbor of Havana, Cuba. A 324-foot armored cruiser that was launched in 1889 but not commissioned in the United States Navy until 1895, the Maine had been sent to Cuba, then a Spanish colony, with a crew of 355 in January 1898 to protect American interests during the ongoing Cuban War of Independence. The morning after the explosion the American public awoke to learn of the tragedy, and concern regarding the fate of the ship’s crew swept across the country, particularly in communities that had a sailor or marine stationed aboard the vessel.

As the nation awaited an explanation for the loss of the Maine, “yellow journalism” newspaper publishers, primarily William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, began to stoke public opinion in favor of war with Spain. On the morning of February 17, however, subscribers to Port Chester’s weekly newspaper, The Port Chester Journal, read a message from the editors that urged caution in the aftermath of the tragedy:

The explosion of the United States Cruiser Maine in the harbor of Havana has given rise to great fears….Over 200 of the firemen and crew are said to be missing. In the conflicting reports and the press censorship exercised, it is difficult to arrive at the cause of the explosion. It seems useless to inflame public opinion by mere guesswork. Our policy is to keep cool. If need be, then to action. 1

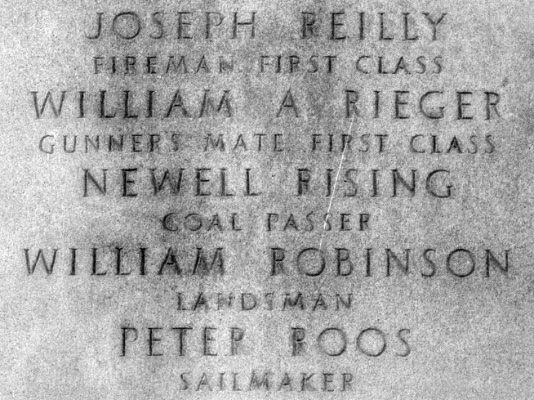

In a kind of postscript to the above passage, the Journal alerted its readers to the fact that a local resident might have been on board the Maine: “It is said that Port Chester was represented on the Maine by a young man named Newell Reising [sic], whose parents reside on Alto Avenue.” 1

The Rising Family

Newell Wade Rising was born on March 18, 1869, to Elihu Rising and Jemima Sanders Boyd. A native of Onondaga County, New York, Elihu Rising was a carpenter and cabinet maker by trade. He served in the Civil War with the 5th Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment. 2 Near the end of the conflict he married Jemima Sanders Boyd, a native of Linlithgow, Scotland, whose first husband, John Boyd, had been killed in action while serving with the 79th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the First Battle of Bull Run. 3 Elihu and Jemima had four children who survived to adulthood: Frances Elizabeth, Newell, Phoebe and William. 4 The Risings moved from New Jersey to Port Chester sometime between 1880 and 1886, and in 1888 Elihu and Jemima purchased a house at 44 Alto Avenue (since renumbered 43 Alto Avenue.) 5

After attending Port Chester schools, Newell Rising learned the trade of a mold maker at the Abendroth Brothers’ Eagle Iron Works. He worked at Eagle Iron Works for several years before moving to Stamford, Connecticut, where he continued to practice his trade. [Newell] Rising did not remain in Stamford for long, as he decided to return to Port Chester where he was hired as a clerk by Wilson F. Wakefield in the latter’s insurance business. Wakefield knew the Rising family well, as he was the former pastor of the North Baptist Church which the family attended.

In the summer of 1896, Rising joined the U. S. Navy at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and was first stationed there aboard the USS Vermont before being assigned to the USS Maine as a coal passer. Frederick T. Wilson, a sailor in the US Navy’s Asiatic Squadron, explained the strenuous work of a coal passer 6 aboard a late-19th century ship:

“When on watch, his duties consist of getting out, or passing, coal to his firemen, and in some ships it is no snap to handle 40 or 45 buckets of coal, each weighing 145 or 150 pounds, in a temperature of perhaps 150° to 175° & has to haul the ashes from the ash pans and load and send up buckets of ashes. He is put to work also at cleaning bilge strainers when they become clogged up with coal dirt and ashes. At times he has to put on the fires when a fireman plays out. He has to stow coal in the bunkers when they coal ship. Has to go in the boilers and knock off scale and scrape out mud, and scale and clean out bilges in port. [He has to] scrub paintwork and paint, clean off pumps, polish bright work, and do any work he may be put at. [He] goes in the back connections of the boilers and cleans out the soot and ashes from there and also in the smoke pipe [and] any old place that is hard to get at and dirty. It is hard an awfully dirty work and it is work that is never done….” 7

By the evening of February 17, the Rising family learned that their son was among the sailors who could not be accounted for and were presumed dead. Like many of his comrades who died in the explosion, Newell Rising’s remains were never identified. He was buried as an unknown, either alongside the USS Maine Mast Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery or in the USS Maine plot at Key West Cemetery in Florida. 8

On February 27, a large assembly crowded the First Congregational Church of Greenwich for a memorial service for Newell Rising. The New York World reported that the church “was not large enough to accommodate the thousands who sought admittance.” 9 Among those in attendance were members of Charles Lawrence Post No. 378, Grand Army of the Republic, of which Elihu Rising was a member. 10 Newell Rising was eulogized by his former employer and pastor, the Reverend Wilson F. Wakefield, who was also Commander of Charles Lawrence Post:

“On the morning of the 16th, as the news came to me that the battleship Maine had been destroyed in the harbor of Havana, I at once said: “Newell Rising is on that ship.” I watched the evening papers to see if he was alive or dead, but when the news came, and confirmed beyond a doubt that he was killed, I went to the home of his parents to join with them in their sorrow and offer condolence in their sad bereavement….

“It was my privilege to know Mr. Rising for several years. We bowed in prayer together in the Baptist Church and labored in the service of God. I believe that it was for the mutual good of both. Newell Rising was of a quiet, unassuming, retiring disposition, never asserting himself without the best of reasons. Industrious and honest, it was but natural that his stewardship for others should have been without question. His integrity was unassailable.” 11

A portion of the cleric’s speech, which was “several times…interrupted by applause,” reflected the nation’s desire for revenge:

If an individual or a set of individuals, or a Government is proved responsible for this disaster, then I say let it be blood for blood, and let the honor of this nation be upheld at any cost. I served in the late war and my brother lost his life for his country. I know what war is, but then a nation’s honor must be upheld. However, I am in favor of peace, but peace with honor combined. 12

Port Chester and The War

A mass meeting was held at Fehrs’ Opera House on King Street on April 8, 1898, to drum up support for the seemingly inevitable armed conflict between the United States and Spain, and to encourage young men to pledge that they would enlist once the war began. The Port Chester Journal reported on the beginning of the meeting:

“The first token of the approaching meeting were the notes of the A.H. Gale Fife and Drum Corps which paraded the streets, awakening the young men as they never were aroused, and when they filed into the Opera House they were followed by a crowd which filled every seat….[W]hile some of the boys were at first disposed to be unruly they were soon in a most favorable disposition, and applauded loudly the speeches that were made and all the references of a patriotic nature.” 13

Captain Eugene L. Swift, an army surgeon stationed at Fort Slocum on Davids Island in New Rochelle, spoke “of the wrongs [America] had suffered at the hands of Spain and the patience we had displayed in resenting her cruel insults,” and “recalled the crimes and outrages that had been charged to the account of that cruel nation and the dastardly proceedings that had at last roused us to action.” 14 The Reverend Wilson F. Wakefield “alluded to the martyred Newell Rising [who] had been murdered on the Maine through Spanish treachery or inaction,” and “then invited all who desired to come up and enroll their names.” The Journal reported that “there was a rush for the stage the astonished even the old veterans” of the Civil War, and about 60 young men affixed their names. The Journal printed a list of the signers in its next issue, less “eight or nine of the names being eliminated by request of parents who refused to permit their sons under twenty-one to bind themselves by their signature.” 13

Congress declared war against Spain on April 25, 1898. A total of 41 Port Chester men served in the armed forces during the Spanish-American War, which concluded with the signing of a Protocol of Peace on August 12, 1898, and the subsequent Philippine Insurrection, which lasted from February 1899 to July 1902. Several of the men from Port Chester who served in the Philippine Insurrection enlisted in a military recruitment office that was opened on Main Street in September 1899. 15

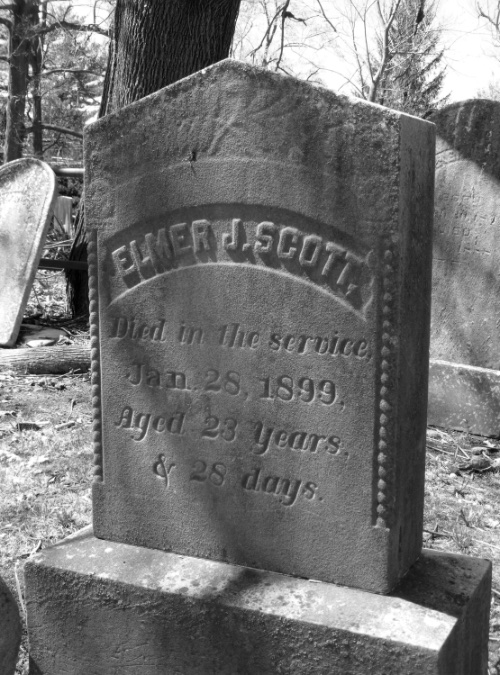

Three Port Chester men lost their lives during the two conflicts. 16 At the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, 22-year-old Elmer Scott was considered one of the most promising young men in Port Chester. The Port Chester Journal highlighted his achievements:

“Elmer Scott was one of the good, bright and energetic lads of our town. Those who will recall the history of our public school for a few years back will remember that he was graduated in one of the most promising classes that ever received diplomas from the district. Elmer Scott received the distinction of that class, by his studious and gifted nature being easily the honor pupil and valedictorian. Those who were present at the closing exercises during which he closed his studies will recall the favorable impression which the modest and unpretentious young man made. His high standing in the class earned him the notice of the leading business men of town, and soon after his graduation he received a position in the First National Bank of Port Chester.” 17

On June 21, 1898, Scott left his position as a bank clerk and went to Stamford, Connecticut, to enlist in Company K of the 3rd Connecticut Volunteer Infantry Regiment. He was appointed corporal in November. The 3rd Connecticut did not see service abroad. While stationed at Savannah, Georgia, in January 1899, Scott contracted spinal meningitis, to which he succumbed on January 28, 1899. 18 After a funeral at Summerfield Methodist Church, Scott’s remains were interred at the King Street Baptist Cemetery.

Nineteen-year-old Walter Corlies enlisted at the Main Street recruitment office on September 12, 1899. He served during the Philippine Insurrection in Company L, 42nd United States Volunteer Infantry Regiment, and was appointed corporal. By early 1901 he had become gravely ill, and was sent across the Pacific to San Francisco, where he died of lung disease at the Presidio on February 12. The Port Chester Journal reported that the voyage “had been too much for him, his desire to reach his native country once more had fed the little life he had, but the effort was too great.” 19 Corporal Corlies’s remains were returned to Saint Mary’s Cemetery in Rye for burial.

A native of Germany, 18-year-old coachman Jacob Fuesguss enlisted at the Main Street recruitment office on the same day as Walter Corlies. He was assigned to Company H of the 42nd United States Volunteer Infantry Regiment. While serving in the Philippines, Fuesguss contracted typhoid fever, and he died at the base hospital at Calamba on March 21, 1900. He was interred at Presidio National Cemetery in San Francisco. 20

Veterans’ Organizations

In the spring of 1899, 18 Port Chester and Rye men who had seen service during the Spanish-American War joined together to form a veterans’ association. Reporting on the formation of this group, The New-York Tribune noted that the men formed “what is believed to be the first post of veterans of the Spanish War.” 21 The association took the name of Newell Rising Post No. 1, Spanish War Veterans. The post made its public debut at a Grand Army of the Republic Memorial Day service at Fehrs’ Opera House on May 28, 1899, during which the veterans were presented with “a handsome stand of colors suitably inscribed and surmounted by an eagle” that had been purchased for them by the Rising family. 22 Two days later the post participated in a procession to the Grand Army of the Republic plot in Greenwood Union Cemetery in Rye, where they paid tribute to the memory of Newell Rising. 23

On February 24, 1900, the Newell Rising Post was mustered into the National Association of Spanish War Veterans. The Port Chester Journal reported that following the mustering-in ceremony, “the sweethearts, wives, sisters and mothers of the young veterans…arranged a royal feast for their entertainment” at the Park Hotel on Liberty Square. 24 The “dancing and mirth” that took place were interrupted only by a moment of silence for Newell Rising, at which time “the silence was so dense that a whisper in any part of the hall could be heard.” 24 Because other posts were mustered into the national organization before the Port Chester association, it was renamed and renumbered Newell Rising Command No. 11.

One of the first events sponsored by Newell Rising Command was a performance of Lincoln J. Carter’s play, Remember the Maine, at Fehrs’ Opera House on March 19, 1900. The Port Chester Journal reported that “the play is supposed to be the plotting of [Cuban Governor Valeriano] Weyler and the Spaniards who blew up the Maine,” and noted that “the true Spanish character is supposed to be revealed in this play which abound[s] in climaxes and thrilling tableaux”:

“The play is given in an elaborate scenic mounting. The battle of Manila is the last act, undoubtedly the greatest battle scene ever seen in this village….Another very effective scene is a representation of the blowing up of the Maine….” 25

A woman’s auxiliary to the command was mustered in on April 16, 1903, and was named Flora A. Lewis Auxiliary No. 5 in honor of the President General of the National Auxiliary of Spanish War Veterans. The 16 charter members of the auxiliary elected Newell Rising’s sister Phoebe as president and Walter Corlies’s sister Margaret as vice president. 26 However, the small membership of Newell Rising Command found it difficult to generate lasting interest in the organization, and in August 1905 it was dropped from the roll of commands recognized by the Department of New York, United Spanish War Veterans, for being in arrears. 27 After a period of inactivity the command reorganized and extended its membership to veterans in Harrison, Mamaroneck, East Port Chester and Greenwich. In January 1908 this group was recognized by the United Spanish War Veterans as Newell Rising Camp No. 68. 28 The woman’s auxiliary was reorganized in March 1910, and Phoebe Rising was again elected as the organization’s president. 29 The Port Chester Journal praised the reconstituting of Newell Rising Camp, noting that the veterans of the National Association of Spanish War Veterans might soon be the principal veterans’ association in the United States:

“Perhaps there is no organization in this or any other section that so nearly approaches the dignity of the Grand Army of the Republic, and since these battle scarred warriors are nearing “recall,” it is most fitting and proper that they should be succeeded by those best qualified to fill the place their “muster out” will make vacant, therefore, in a word, the veterans of the Spanish-American War have a duty to perform, and that duty is to organize as will insure the perpetuation of the memory of those who laid down their lives on our country’s altar.” 30

Among the trustees of the reconstituted camp was William A. Darcey, a native of Vermont who served in the 1st Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the Spanish-American War and moved to Port Chester in 1903. After serving as a reporter for The Port Chester Item for six years, Darcey became editor and manager of The Rye Chronicle in 1909. He would lead the effort to memorialize the Spanish-American War and the Philippine Insurrection in his adopted village. 31

Memorializing Newell Rising

The leadership of Charles Lawrence Post No. 378, Grand Army of the Republic, first voiced the idea of a memorial for Newell Rising only a few days after the loss of the USS Maine. The members of the post met shortly after hearing of Rising’s death and declared their intention to create a memorial for him:

“Beyond the present dark horizon a silver bow appears full of hope and promise to cheer all bowed down with grief. At the last general muster the Great Commander will unite the family and Newell Rising, the sailor, martyr, and son of a veteran, will respond with joyous alacrity to the roll call—“here.” Resolved…[that] a suitable memorial be erected in the G.A.R. burial plot in Greenwood Union Cemetery in commemoration of the sad event.” 32

Lawrence Post arranged for the creation of a special tablet that would be affixed to the monument that stood in the center of their burial plot. The tablet was designed by George Beck, an architect and designer who was employed at Eagle Iron Works and knew Newell Rising well from his days at the company. 33 The cost of the tablet was borne by Lawrence Post and several of Rising’s former co-workers from Eagle Iron Works. 34 On Memorial Day, May 30, 1898, the tablet was dedicated with appropriate ceremony. The Port Chester Journal noted that “the weeping mother of Newell W. Rising and his sisters” were among those who were deeply moved by the proceedings. 35 Dedicated a mere three months after Rising’s death and nearly a month before American forces landed in Cuba, this tablet was one of the first memorials in the United States created in response to the loss of the USS Maine.

Newell Rising’s loss was recognized twice on Memorial Day, May 30, 1902. During ceremonies at the Grand Army of the Republic plot in Greenwood Union Cemetery, a wreath was placed around his memorial tablet. Later a second ceremony was held along the Byram River at the east end of Westchester Avenue, as The Port Chester Journal reported:

“In accordance with the suggestions of General Orders from National Headquarters [of the Grand Army of the Republic], that full honor be done the sailors who died and were buried at sea, by strewing flowers in the waters flowing out to the sea, a number of Charles Lawrence Post after the proper salutes and decorations in the various cemeteries, went to Lyon’s Point, accompanied by the Ladies’ Auxiliary or Woman’s Relief Corps, and there reverently dropped into the ebbing tide of the Byram River a profusion of flowers in memory of our own local Newell Rising who perished on the Maine in Havana Harbor and the gallant heroes of the Rebellion.” 36

During the first decade of the 20th century, momentum built for the establishment of a public monument to Newell Rising within the limits of the village of Port Chester. The drive to create a monument was led by three members of Newell Rising Camp No. 68: William A. Darcey, Charles W. Stevens and Homer B. Smith, Jr. The veterans chose Summerfield Park, a small parcel between King Street and Willett Avenue, as the location for the memorial. The New Rochelle Pioneer described the monument, which was built in only a few weeks:

“The monument will consist of [a] ten inch shell apportioned to Port Chester as a relic from the ill-fated Maine, mounted upon a base of rough faced stone, standing six feet high [and will] make a very creditable tribute to the long neglected sailor who went down with his ship. The shell weighs one thousand pounds. The base will be four feet square at the bottom, and taper to about fifteen inches at the top. On one side of the base a tablet will be inserted, made of bronze.

“At the base of the monument and extending about four feet in each direction, will be a walk, forming a Maltese cross, which is the emblem of the Spanish War Veterans. The monument will be set true to the points of the compass, and each part of the cross will contain a letter, set in brass, indicating the direction. This is the same as the obverse side of the Spanish War Veterans’ emblem, and is indicative of the fact that the Spanish War drew men from all points of the compass, to the defense of the Nation.” 37

The monument to Newell Rising was dedicated on July 4, 1912. The dedication ceremony was preceded by a parade featuring 1,500 soldiers from Fort Slocum in New Rochelle, National Guardsmen, and members of veterans’ organizations. The colors were hoisted up a newly erected Liberty Pole next to the Rising monument by Port Chester resident Nicholas Fox, a Civil War Medal of Honor recipient. 38 Jemima Rising, mother of the deceased sailor, unveiled the monument to her son. New York State Senator Jonathan Mayhew Wainwright delivered the oration at the unveiling, and concluded his address with a note of thanks to the federal government, which had provided the shell from the USS Maine:

We accept this relic with gratitude, for it will be one of the treasured public possessions of this village and of our town as long as this stone and metal shall endure. I dedicate this ten inch shell from the “Maine” to Newell Rising and the men who died with him. Let it stand for valor and duty! 38

The shell from the Maine was not the only relic from the ill-fated warship to appear in Port Chester. In June 1913, a deck plate from the ship was sent to the village and put on display in the show window of H.B. Smith Company at 120 North Main Street. This business, which was opened in 1894, was known as the “Port Chester Cash Bargain House,” and was owned by Homer B. Smith, father of Rising Camp member and Port Chester Village Treasurer Homer B. Smith, Jr. 39 A reporter from The Rye Chronicle noted that the artifact “somewhat resembles a large bolt and the under side is covered with sea shells.” 40

Newell Rising’s memory remained vivid among the Spanish-American War veterans of Westchester. On February 23, 1914, his sister Phoebe married Joseph P. Murray, Jr., of Mount Vernon in a Roman Catholic ceremony at Saint Joseph’s Seminary in Yonkers. The nuptials were officiated by Father John P. Chidwick, chaplain of the USS Maine at the time of the ship’s destruction. The wedding was attended by members of Mount Vernon’s William R. Carmer Camp No. 8, United Spanish War Veterans, of which the groom was a member. Phoebe Rising was attended by officers of Flora A. Lewis Auxiliary No. 5. The front page coverage of the wedding in the Mount Vernon Daily Argus was headlined “Local Man Weds A Sister of Maine Hero.” 41

A New Monument

Members of Newell Rising Camp held ceremonies at Summerfield Park each February 15th, the anniversary of the destruction of the USS Maine. 42 However, many members of the veterans’ organizations in Port Chester felt that a monument should be created to memorialize all of the residents of the village who answered their country’s call during the Spanish-American War and Philippine Insurrection. William A. Darcey, who again answered his country’s call in 1917, serving as a training officer stateside and achieving the rank of major by the end of the conflict, spearheaded the movement to establish such a monument in Summerfield Park. 43 As chairman of the Universal Memorial Day Observance Committee for Port Chester and the Town of Rye, Darcey presented a plan for such a monument to the Port Chester Board of Trustees and Park Commission in July 1935.

The memorial that Darcey and his fellow veterans proposed was to be constructed in two phases. First, two granite bases of differing sizes would be constructed in Summerfield Park. The smaller base would support the shell from Newell Rising’s monument, and it would be dedicated to the martyred sailor. The larger base would list the names of all the men from Port Chester who served in the Spanish-American War or in the Philippine Insurrection. Once the bases were finished, a statue of a soldier was be carved out of a granite block and placed atop the larger base.

Port Chester architect Louis A. Settino agreed to design the granite bases for free, and Ogden Mills Reid, proprietor of The New York Herald Tribune and owner of Ophir Hall in Purchase, agreed to donate the necessary granite for the bases. Darcey believed that if the village were successful in getting Works Progress Administration funding through the Federal Art Project, the monument would only cost the municipality $1,500. 44

Port Chester’s village officials were wary of a new war memorial, and past experience gave them good reason to be concerned. The Soldiers’ Monument erected in 1897 to the Civil War veterans of Port Chester and Rye was not dedicated until 1900, due to a dispute with the Grand Army of the Republic over the design of the memorial, which featured the statue of an officer, Lieutenant Colonel Nelson B. Bartram, rather than an enlisted man. 45 The committee that was responsible for Port Chester’s World War I monument did not consult village officials regarding the memorial’s cost and design. As a result, the municipality was still paying off the $40,000 monument in 1936, five years after it had been dedicated. 46

Nevertheless, Port Chester officials felt that it was time to make appropriate improvements to Summerfield Park. Ernest Capeci of the Port Chester Parks Commission claimed that “people walk all over the place, grass never grows there and it looks like the dickens.” 47 Village officials were also pleased to learn that federal funding would be provided for the project. On March 4, 1936, the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration agreed to allocate $8,147 to Port Chester for labor to carve the granite bases of the memorial. 48 Work on the bases began six days later. The Port Chester Daily Item described architect Settino’s plans for the bases:

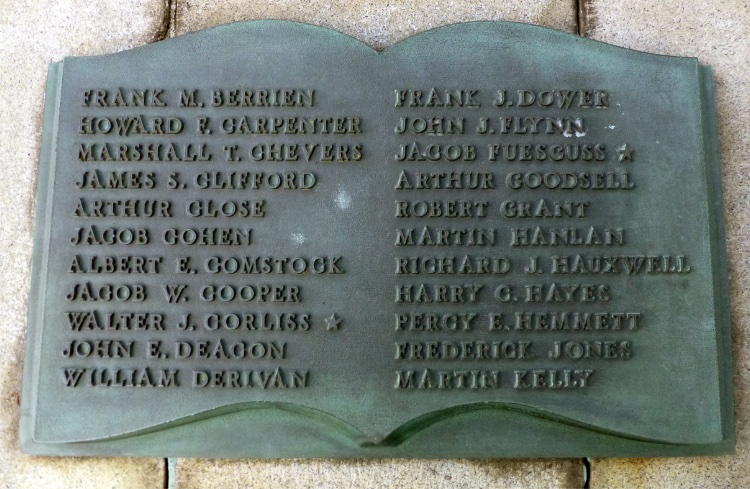

“The monument…will be composed of a granite dais supported by four granite pedestals, appropriately carved. Leading to the dais from the north, south, east and west sides will be four stairways of four rises each, all of granite. In the middle of the concrete walk, facing Summerfield Methodist Church, will be the Newell Rising memorial, a slab of concrete topped by a shell. Topping the four pedestals will be bronze tablets of the Spanish War veterans who enlisted from Port Chester.” 49

As work began on the memorial’s two bases, attention turned to proposals for the statue that was to be the centerpiece of the monument. Desiring to provide work for local artists, Federal Art Project officials were only able to find two sculptors in the vicinity of Port Chester who possessed the ability to design such a large statue. Noting that he had too many prior commitments, one of the two sculptors declined to submit a model for consideration. Therefore, it seemed a given that the other artist, Karl Illava of Greenwich, would design the statue for Port Chester’s Spanish-American War monument—provided, of course, that the WPA approved his model. 50

Karl Illava

Born Karl Morningstar on March 17, 1889, Karl Illava attended Barnard High School for Boys in Washington Heights and the Kingsley School in Essex Falls, New Jersey.51 At the age of 16, Illava decided to abandon the traditional educational route and devote his life to art. He became a pupil of Gutzon Borglum, who would later earn world renown as the sculptor of Mount Rushmore. Five years later, Karl adopted the surname Illava (occasionally given as Pavany-Illava), which had been the surname of his paternal grandfather prior to the latter’s arrival in the United States from Hungary.52

Illava quickly gained a name for himself as one of New York City’s most promising young sculptors. In December 1915, one of his sculptures, a “black hand clutching a mass of something from which falls a golden dollar,” was exhibited at a show entitled “Immigrant in America” at Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s studio. One of the visitors to the show was former President Theodore Roosevelt, perhaps the most celebrated figure from the Spanish-American War. Roosevelt’s comment on Illava’s work was one that many felt could apply to the sculpture that the artist would one day create for Port Chester: “Very strong, very strong. Unpleasant, but true—true in part, no doubt.” 53

In January 1914, Illava enlisted in the New York State National Guard. From June 1916 to January 1917, he served with the National Guard’s 1st Cavalry as part of the “Pancho Villa Expedition” that had been organized to capture the eponymous Mexican leader after his raid into New Mexico.54 Following America’s entry into World War I, the New York National Guard was activated and became the 27th Infantry Division. Prior to departing for Europe, the division was sent to Camp Wadsworth in Spartanburg, South Carolina, for training. It was here that Illava’s first military artwork was created, when he was called upon to brighten the inside of an officers’ mess hall. He covered the hall’s “dull, raw pine walls” with “a shimmering mantle of buff and blue, the cavalry colors, while about the border near the ceiling there pranced and cavorted fiery chargers with their soldier riders, done in silhouette.”51 The work impressed Illava’s superiors and was praised by citizens of Spartanburg who visited the camp.

Illava served in the 27th Infantry Division throughout World War I, spending eight months in Europe prior to being discharged in February 1919. He then returned to the Manhattan studio that he shared with Gutzon Borglum at 166 East 28th Street.51 Several months later he received a major artistic commission that came directly as the result of his wartime service. The City of Spartanburg, which remembered Illava’s work at Camp Wadsworth, chose him to create the municipality’s Great War monument. The resulting memorial featured two soldiers, one each from the 27th Infantry Division, which consisted of soldiers from New York, and the 30th Infantry Division, which was comprised of National Guardsmen from North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia. The New York Times review of Illava’s Spartanburg monument foreshadowed the controversy that would surround his monument at Port Chester:

“To those who admire the trim figures leaning in military attitude on their rifles—those common figures which every country town bought in the late sixties—Mr. Illava’s monument for Spartanburg may not prove attractive. Rather, there may be a shock to the feelings of such persons as look with reverence at the product of decades ago, for in the monuments of the Civil War there is generally an attempt to show the American soldier as one whose shoes never lost the shine required at inspection, whose clothes never lost the smartness reserved for nights in town, who was never tired, unless the posture of “parade rest” could indicate a physical weakness.”55

In 1920 Illava married Agatha Brown, with whom he had two daughters, Faith and Mary.56 In 1922 he sculpted a World War I monument for Dickinson High School in Jersey City, and the following year he created a Great War memorial for the city of Gloversville, New York. The latter monument, The Thinking Doughboy, featured “a colossal seated figure of a doughboy, bent in thought, contemplating his trophy, a German helmet.”57 The New York Times noted that Illava “tried to express [the] quiet disillusionment” felt by the victorious soldier.57 As he had done with his Spartanburg monument, Illava attempted to create a sculpture that reflected the effects of war on the common soldier.

On September 3, 1925, the Illavas acquired an acre of land at 825 Hartsdale Road in Greenburgh. The deed that executed this sale noted that the property included “a two and a half story cement block studio.”58 This structure had been constructed about 1908 by Riccardo Bertelli, founder and owner of Roman Bronze Works in New York City. The west half of the building featured a two-and-a-half-story studio, while the east half contained living quarters. The studio had previously been owned by Henry Merwin Shrady, who had sculpted the Ulysses S. Grant Memorial on the west side of the United States Capitol.59

By the time Illava moved to Greenburgh he was recognized as one of the premiere sculptors in the New York metropolitan area. In 1928 and 1929 he served on the jury which selected the fine arts prize recipients of the William E. Harmon Foundation Awards for Distinguished Achievement Among Negroes, better known as the Harmon Foundation Awards or the Harmon Awards.60

As his fame grew, Illava received requests to teach art classes. At first he only taught children of friends, but in the fall of 1930 he opened his Greenburgh studio once a week to teach a group of children from Scarsdale.61 Illava’s classes became so popular that the following year he began to teach courses at the Westchester Workshop, a program sponsored by the Westchester County Recreation Commission at the Westchester County Center. His courses included sculpture and art appreciation, the latter of which qualified for credit at New York University. Illava also displayed his work at art exhibits sponsored by the Westchester Workshop.62

While residing in Greenburgh, Illava designed what would become his best-known work, a monument honoring the 107th Infantry Regiment. This unit was part of the 27th Infantry Division during World War I. In January 1927, Illava placed the finished plaster model of the monument on exhibit at his Greenburgh studio.63 The four-ton bronze monument that resulted from this model was placed in Central Park at 5th Avenue and 66th Street. It was unveiled on September 29, 1927, the anniversary of the day on which the 107th broke through the Hindenburg Line at St. Quentin Canal in France.64

In June 1931, the Illavas sold their Hartsdale Road property and moved to Sagamore Road in Bronxville. Many residents of Bronxville were eager to learn from their new neighbor, and in October 1932, Illava partnered with two fellow artists to open the Forum School of Art at 80 Palmer Avenue.65 Illava did not remain active in Bronxville for long. During the 1935-1936 school year he took a position as an art instructor at the Edgewood School, a private institution in Greenwich, Connecticut. By the time Illava was selected to design a monument for Port Chester, he had apparently closed the Forum School of Art and had relocated to Greenwich.

The Big Soldier

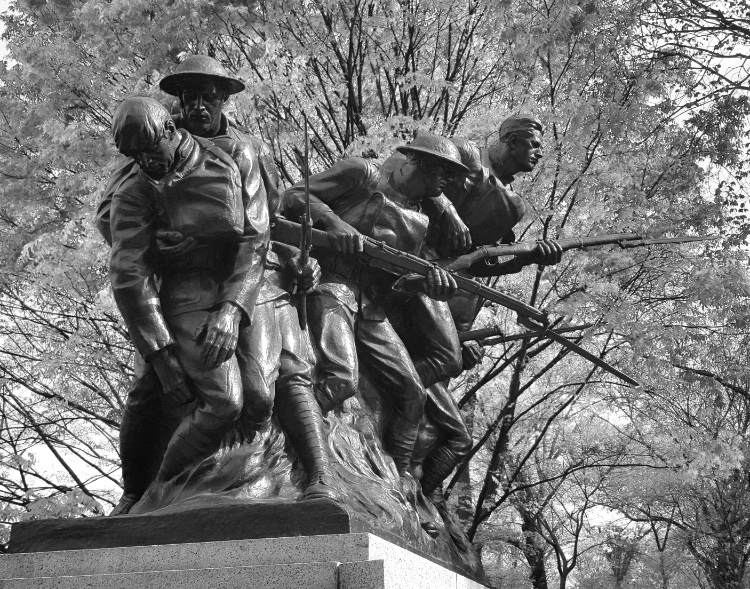

During the spring and early summer of 1936, Karl Illava worked on his sculpture at the old New York and Stamford Railroad trolley barn on Midland Avenue in Port Chester.66 The finished model, The Big Soldier, was unveiled on July 21, 1936. As Illava was on vacation in Massachusetts, his assistant, Kurt Biener, unveiled the clay figure at the trolley barn.67 The New York Times provided a description of the model:

The figure is 9 feet 6 inches high and represents an exhausted soldier in tattered uniform standing at rest with his legs spread wide, a rifle under one arm and the other hand pressed against his abdomen. The head appears somewhat small, the shoulders of unusual breadth, the arms long and the hands huge.67

The Bronxville Press commented that “not only the ungainly proportions of the figure, but also the features express the opinion that war is what General Sherman said it was during the Civil War—or worse.”68 Karl Biener explained that the statue was meant to reflect the reality of war:

At the first glance almost every one would start up as if with horror, but every one went away saying that the statue should be put up to show what war really is. They don’t want just one more statue, they said, just another figure to glorify war. They all said they thought it was a real piece of art, and they were people of all classes.67

Walter Praray, a former commander of Rising Camp who had served in the 1st Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the Spanish-American War, believed that the statue appeared “just the way a soldier looked coming up a hill in the War of ’98”:

There was nothing beautiful in the war. This statue is alive. The soldier is perspiring; he has just come over a hill; he is tired out, hungry and unhappy. He shows it. It is a great peace monument. It shows what happens when you put a gun in the hands of a young man. It makes him a brute.69

William A. Darcey agreed that the statue accurately reflected the horror of armed combat, noting his belief that “there is nothing more asinine” to his fellow veterans than “to see a statue of a soldier in the act of bayoneting an enemy with a cherubic smile on his face, or clothed in a dress parade uniform.”70 Calling the sculpture a “magnificent creation,” Darcey explained that “the idea of the statue is to show war as it really was during the Spanish-American War, and that’s just what it does….All the Spanish War Veterans are for it.”71

Illava agreed to address Darcey’s one minor objection to the model: he consented to “remove the Grecian head and substitute one with American features.”68 The day after the unveiling the Port Chester Daily Item published a photograph of the model on its front page. Used to idealized figures of soldiers such as the statue on their village’s Civil War monument, many residents of Port Chester were somewhat taken aback by The Big Soldier. Chief among those who were skeptical of the model was Port Chester Mayor William Burdell Banister, who told The Daily Item that he thought the statue was “ugly,” and “wouldn’t have it on any property of mine.”72 However, Mayor Banister noted that he was a “layman,” and stated that he would “rather call in two or three artists who could give us an expert opinion.”73

Before the Port Chester Board of Trustees paid a visit to Illava’s studio in the trolley barn, a great debate regarding The Big Soldier took place among the residents of the village. On July 25, The Daily Item published two letters to the editors regarding the model. Alice M. Quinn, a musician and mother of five, argued against The Big Soldier:

“I fail to see where the utterly grotesque and repulsive figure shown in the Daily Item could call forth any reaction other than disgust from anyone who had the misfortune to view it. Are we erecting a reminder of the horrors of war, or are we honoring the spirit of sacrifice shown by those who have passed on? If the latter is true, no matter what our personal opinion of war may be, is not this spirit of sacrifice worthy of a monument of beauty?”74

The Reverend Theodore Parker Ferris, an Episcopal priest and son of Westchester County District Attorney Walter A. Ferris, addressed his support of the monument to Mayor Banister:

“As one who was raised and educated in the schools of Port Chester, I cannot refrain from asking the Mayor—can anything representing war and the ravages of war be too ugly? To whom is war not distasteful? Are there any who remain victims of the illusion that war is glorious? If so, and if this statue can shatter that illusion, let it stand where every man, woman and child can see it. If it opens our children’s eyes to the realities of war, the horror of it and the impotence of it, is that a bad effect? Or shall we keep them in the mists of a vague and unreal patriotism which may stir their blood but deaden their minds and kill their spirits?”74

Some of Illava’a fellow artists objected to the sculptor’s work. Henri Crenier of Mamaroneck, who was in the process of sculpting a statue of Christopher Columbus for his village’s Columbus Park, stated that his own statue was “a protest against the new art such as is being done in Port Chester.” Crenier expressed his feelings that “art is beauty and something that is not beauty is not art,” and that “those who distort primitive beauty are merely publicity seekers.”75

A group of Port Chester village officials visited the trolley barn on July 25 to inspect the model in person. Seeing the model up close turned Mayor Banister firmly against The Big Soldier. Calling the figure a “monster,” the mayor declared that the work was not “a proper statue for one of our parks,” and felt that the work was not appropriate for the park:

We need to beautify our parks and not put up scarecrows like this. There is nothing beautiful about it….There is something communistic about it as a whole that I don’t like.76

While members of the village board prepared to vote on The Big Soldier at their next meeting, members of veterans’ groups as well as the public at large weighed in on the controversial design. Some, such as John W. Diehl, president of the Port Chester Savings Bank, opposed the statue on aesthetic grounds and felt that it would reflect poorly on the municipality’s image. Diehl believed that the many travelers who passed through the village would not take the time to properly reflect on the monument, and “consequently [would] remember Port Chester as the town with the ‘horrible looking’ statue in the park.”77 Dr. Orville McKim, a veterinarian who served in World War I, declared that the statue “may portray war as it is, but I should hate like the dickens to have my service depicted by such a monument.”78 However, Theodora Capeci, a case worker for the Westchester County Department of Social Services, felt that “a war memorial should be an expression of realism of one who has felt its horror,” and stated her belief that “if men have withstood such horrors of war, our feminine eyes should be able to withstand such a ‘monstrosity of art.’”79 The editors of The Daily Item approved of the statue, as they trusted in the opinions of the veterans and the artistic ability of Karl Illava.80

On July 28, a reporter from The Daily Item visited the annual dinner of the Port Chester Chamber of Commerce to take an unscientific poll of the village’s leading businessmen. Of the 26 who expressed opinions, 19 were against the model, five were in favor and two were neutral. Opinions ranged from that of Charles E. Kelly of the Rye Ridge Development Company, who grumbled that the statue was “atrocious” and “look[ed] like Frankenstein,” to that of Louis Hurwitz, a jeweler, who declared, “It makes war hideous. Therefore I am in favor of it.”81

The following day a delegation of WPA authorities and Federal Art Project officials visited Port Chester to see the statue for themselves.82 The group included three art experts: Professor George William Eggers of CUNY; Carl Paul Jennewein, a sculptor and member of the Municipal Art Commission of New York; and Emily F. Genauer, art critic of The New York World-Telegram. Although Professor Eggers remained silent, Jennewein opined that Illava’s sculpture was “bad art,” while Genauer called the work a “lousy sculpture.”83

The WPA delegation also viewed a second, smaller model that Illava had created. This sculpture depicted a “soldier standing erect, with legs apart, a rifle held in his right hand with the muzzle touching the ground near the left foot and a knapsack around the upper part of his body.”84 The group acknowledged that it was “familiar with the work of” Illava but “disapproved on aesthetic grounds” the larger of the two models. When word of the group’s rejection of The Big Soldier reached Illava in Massachusetts, he promptly wired a telegram back to Port Chester:

Greatly disappointed. Faith in Port Chester and my big soldier unshaken. Reactionary forces too strong for progressive art. Criticism by WPA unjustifiable. Its function should be relegated to that of timekeeper and paymaster. None has right to interfere with artist in freedom of expression. Congratulations to all war veterans for courageous stand.85

Illava then composed a letter to The Bronxville Press criticizing the WPA and defending The Big Soldier:

I’m an ex-soldier. I believe I know something of war. General [John F.] O’Ryan, under whom I served in the Mexican campaign and in the A.E.F., once said, “I believe you sculptors are as responsible for war making as any other stratum of society”—or words to that effect. Why do you glorify it? Why don’t you tell the truth about it? The Port Chester Soldier is a symbol. It represents war the way I feel it. How else can an artist work?86

On August 3, the Port Chester Board of Trustees formally rejected The Big Soldier. Before the board came to its decision, WPA employees had been using spray guns and sponges to keep Illava’s clay model moist. Upon hearing that the village had rejected the design, the employees stopped their work, and on August 12, the five-ton model crumbled and fell apart.87 Progress on the granite base in Summerfield Park had also stalled, as the WPA was not able to obtain the services of skilled workers. Architect Louis J. Settino, designer of the granite base, told The Daily Item that “stone cutters are rushing to private jobs, and as a result we have been left with only one man working daily whereas we anticipated having at least nine.”88

The Disconsolate Soldier

Undeterred, William A. Darcey asked Karl Illava to submit a new model for the statue. The artist went to work on a new design in late August, but told Darcey that he would only submit a model directly to the Port Chester Board of Trustees and would not be part of any kind of WPA-sponsored competition:

“I’m getting to work on your soldier today. I have a swell idea. I’m so pleased with myself that I’m consoled and am now half glad that [the Board of Trustees and the WPA] rejected my Big Solder. I’ll show Port Chester and its Mayor that old soldiers never die. But I want a guarantee that under no circumstances am I competing.”89

Meanwhile, officials from the Federal Art Project put out a new call for designs. While communication between the WPA and Port Chester appears to have been lacking, one thing was made quite clear: the WPA would not permit Karl Illava to submit a new model. In a letter to Mayor Banister, William Owen of the Federal Art Project explained that “since Mr. Illava has resigned from the project of his own free will…it would not be possible for [him] to do this work unless he were put back on the project, which it would be practically impossible for me to do.”90

Officials from Port Chester viewed two models at the Federal Art Project office in Manhattan on November 12, 1936. One was judged by a reporter from The Daily Item as “a youthful looking soldier giving aid to a wounded companion,” while the other was described a “brutish looking design more on the type of [Illava’s] ‘Big Soldier.’”91 The Port Chesterians went home disappointed, with Mayor Banister complaining that he had “been promised five or six subjects to select from.”91

Noting the frustration of village officials with the WPA, the Spanish-American War veterans encouraged Illava to bypass the Federal Art Project and submit his new design directly to the Port Chester Board of Trustees. Several village officials, including some who disapproved of The Big Soldier, spoke favorably after viewing Illava’s new model on November 30. However, the veterans’ plan was nixed, for one week later the WPA sent a letter to the Port Chester Board of Trustees reiterating its opinion that Karl Illava should not be permitted to submit any proposal.92

Port Chester village officials again visited the Federal Art Project headquarters in Manhattan on February 8, 1937, to view three WPA-sponsored models. One of the models, Broken Sword, featured “a figure in laboring clothes” who was “breaking a sword while gazing on the form of a dying soldier.” This model was criticized by the officials as “having a socialistic trend,” and was rejected along with the other two designs.93

Disappointed with the models presented by the WPA, the Port Chester Board of Trustees decided to invite three sculptors to submit designs directly to them rather than to the Federal Art Project. The three sculptors were Karl Illava; Luigi Del Bianco of Port Chester, who had recently served under Gutzon Borglum as the chief stone carver at Mount Rushmore; and Henri Crenier, the same sculptor who had harshly criticized The Big Soldier. On April 19, 1937, the Port Chester Board of Trustees unanimously chose Illava’s new model, which the sculptor titled The Disconsolate Soldier.94 Pleased that his work had been accepted, Illava told The New York Herald Tribune that he hoped his statue would mark a change in the kinds of war memorials erected in the country:

I would not compromise on a statue which is to give a realistic conception of war. The day of the waving flag statue is past and, so far as I am concerned, there is nothing more typical of war than the tired and disillusioned solder.95

The Port Chester Board of Trustees originally intended to have the statue sculpted from a large, 17-ton granite block that had been sitting in Summerfield Park since the fall of 1936.96 However, the lack of WPA funds meant that carving a granite sculpture would be too expensive for the village. Therefore, the trustees chose a less costly option and contracted with Kunst-Nieder, Inc., of New York City, which submitted a low bid of $1,000 to produce a bronze statue from Illava’s model.97

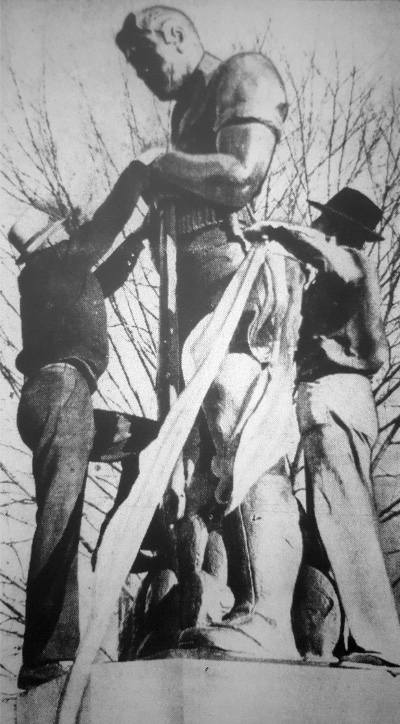

On November 9, 1937, the 9-foot-tall, 1,500-pound statue was placed atop its pedestal in Summerfield Park in front of 100 curious onlookers. Viewing the finished product of his work, Illava expressed his feelings to The Daily Item:

“It’s better than I thought it would be on such a base although not exactly as I would want it to look. But then, again, we artists are never quite satisfied.”96

The statue cost Port Chester $2,560. Karl Illava’s design fee came to $1,500, while $1,060 was spent in creating the statue and transporting it to Summerfield Park.98 A crowd of over 1,000 was present on April 25, 1938, when Port Chester’s Spanish-American War memorial was finally dedicated after more than two years of work. The ceremony was preceded by a parade in which National Guard units, American Legion posts and United Spanish War Veterans posts from New York City, Brooklyn, New Rochelle, Mount Vernon, Peekskill, Long Island and Stamford participated. Newell Rising’s sister Frances Elizabeth placed a wreath at her brother’s monument, while Adjutant General John J. Fitzpatrick of the Untied Spanish War Veterans laid a wreath in front of the new monument. The Daily Item reported that Fitzpatrick urged “the revival of the ‘same spirit of love for our country and patriotism which led the men you are fittingly honoring here today to answer their country’s call in ’98,’ as a means of stamping out Communism and ‘other isms’ in America today.”99 This comment was especially relevant, as that same day the Westchester-Connecticut Bund held its annual German Day celebration at the Westchester County Center. Under the headline “Nazi Salute Greets Marching Men In County Center Celebration,” The Daily Item ran a photo of a large crowd with arms extended saluting the American and German flags next to the column reporting on the dedication of the Spanish-American War monument.

Aftermath

Karl Illava appears to have had little connection with Westchester County after the unveiling of The Disconsolate Soldier. Following the outbreak of World War II, the 55-year-old artist attempted to enlist in the U.S. Army, but he was turned down due to his age. Determined to participate in the war, Illava offered his services to the United States Merchant Marine. The New York Evening Post reported on how the sculptor entered his third armed conflict in the fall of 1943:

“[Illava] went to the employment headquarters of the Maritime Service. “Which do you need, cooks or pursers?” Secretly, he hoped it would be purser. “Cook,” they screamed in reply. “Cooks are very important,” he explains in his gentle cultured voice, explaining it as much to himself as to you. “Those boys need good food well prepared. If I must say so, I can make a whangdoodle of a stew. The secret is—no water.””100

After his Merchant Marine service came to a close, Illava returned to the Edgewood School, where he taught art and sculpture until his death on May 16, 1954. Illava’s Greenburgh studio was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1982, due to its use by sculptor Leo Friedlander, who owned the building from 1934 to his death.101

Frances Elizabeth Rising, the last member of the Rising family to reside in Port Chester, died in 1944.102 Membership in Newell Rising Camp No. 68, which numbered 35 in 1935, had declined to 10 by 1955, and the camp was disbanded on November 16 of that year.103 The last two surviving members of the camp were the two who fought the hardest to place a Karl Illava sculpture atop their village’s Spanish-American War monument. William A. Darcey died on October 31, 1966, at the age of 90. For several years Darcey was given the honor of leading Port Chester’s parades, due to his status as the village’s oldest veteran. Ill health forced him to cease this activity around 1960. Walter Praray, who moved to a veterans’ hospital in Bath, New York, about 1967, appears to have been Newell Rising Camp’s last surviving member, dying on April 3, 1970 at the age of 91.104

The loss of the USS Maine has since been overshadowed twice by events that shocked the American public and led to war: the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. United Spanish War Veterans, once viewed as the successor to the Grand Army of the Republic, became the principal veterans’ organization in the United States. Within two decades of its founding, however, it was overtaken in membership by the Veterans of Foreign Wars and the American Legion, as World War I superseded the Spanish-American War as the United States’ most recent armed conflict. However, the two monuments in Summerfield Park still stand as a reminder of Port Chester’s desire to memorialize a son of the village who lost his life in one of the US Navy’s most tragic peacetime events and to recognize its young men who answered their country’s call to arms in the “Splendid Little War.”

- “Keep Cool.” The Port Chester Journal, 17 February 1898.[↩][↩]

- Gale J. Brunner. Genealogy of the Rising Families of America (Burlington, MA: Goodway Graphics of Massachusetts, 1981), 176. “His Death Caused By Old Age.” The Port Chester Journal, February 2, 1911.[↩]

- Ibid. “Wife And Mother Of War Veterans Dies Aged 86.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., April 25, 1924.[↩]

- Ibid. Jemima Boyd also had at least two daughters and one son with her first husband.[↩]

- Westchester County Land Records Liber 1150, 298-302. “Obituary: Mrs. Phebe P.R. Murray.” The Daily Argus, Mount Vernon, N.Y., April 17, 1935.[↩]

- http://www.westchesterhistory.com/index.php/publications/best#text_4[↩]

- James R. Reckner. A Sailor’s Log (Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 2004), 16.[↩]

- “Dead and Wounded.” The Washington Post, February 18, 1898.[↩]

- “Services for Victim Rising.” The New York World, February 28, 1898.[↩]

- “Westchester County.” The New-York Tribune, February 28, 1898.[↩]

- Memorial Service to the Young Hero of the Maine.” The Port Chester Journal, March 3, 1898.[↩]

- “In Honor of Newell Rising.” The Sun, New York, N.Y., February 28, 1898. Arthur Russell Wilcox. The Bar of Rye Township, Westchester County, New York (New York: The Knickerbocker Press, 1918), 135-136.[↩]

- “The Mass Meeting Patriots.” The Port Chester Journal, April 14, 1898.[↩][↩]

- Ibid. “The United Service.” The New York Times, June 19, 1898.[↩]

- “The Boys Recruited In The Army.” The Port Chester Journal, September 14, 1899.[↩]

- “Spanish War Memorial To Honor 41 Men.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., August 1, 1936.[↩]

- “Death of Elmer J. Scott.” The Port Chester Journal, February 2, 1899.[↩]

- Record of Service of Connecticut Men in the Army, Navy and Marine Corps of the United States in the Spanish American War, Philippine Insurrection and China Expedition (Hartford, Conn., Press of the Case, Lockwood & Brainard Company, 1919), 145. “Death of Elmer J. Scott.” The Port Chester Journal, February 2, 1899.[↩]

- “One of Our Volunteer Soldiers Die.” The Port Chester Journal, February 14, 1901. Walter Corlies card, New York Spanish-American War Military and Naval Service Records, Ancestry.com.[↩]

- Jacob Fuesguss card, New York Spanish-American War Military and Naval Service Records, Ancestry.com.[↩]

- “Westchester County: Port Chester.” The New-York Tribune, May 30, 1899.[↩]

- “The Opera House Memorial Services.” The Port Chester Journal, June 1, 1899. “Westchester County: Port Chester.” The New York Times, May 30, 1899.[↩]

- “Memorial Day in Union Cemetery.” The Port Chester Journal, June 1, 1899.[↩]

- “Newell Rising Command Mustered In.” The Port Chester Journal, March 1, 1900.[↩][↩]

- “Remember the Maine.” The Port Chester Journal, March 15, 1900. “Little of Everything.” The Port Chester Journal, March 22, 1900.[↩]

- “Woman’s Auxiliary Spanish War Veterans.” The Port Chester Journal, April 23, 1903.[↩]

- Documents of the Assembly of the State of New York, One Hundred and Thirty-Fourth Session (Albany, N.Y.: J.B. Lyon Company, 1911), XXIV, 79-80.[↩]

- “Spanish War Veterans to Reorganize.” The Port Chester Journal, January 16, 1908. “Spanish War Veterans Reorganize.” The Port Chester Journal, January 23, 1908.[↩]

- “Auxiliary U.S.W.V. Elect Officers.” The Port Chester Journal, March 24, 1910.[↩]

- “Spanish War Veterans to Reorganize.” The Port Chester Journal, January 23, 1908.[↩]

- “Spanish War Veterans Reorganize.” The Port Chester Journal, January 23, 1908. “Maj. Darcey, 90, Dies; Spanish War Veteran.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., October 31, 1966.[↩]

- “Celebration by the Veterans.” The Port Chester Journal, February 24, 1898.[↩]

- “A Fitting Memorial.” The Port Chester Journal, May 19, 1898.[↩]

- “To Dedicate Tablet.” The Chronicle, Mount Vernon, N.Y., May 27, 1898.[↩]

- “Memorial Day.” The Port Chester Journal, June 2, 1898.[↩]

- “Memorial Day in the Vicinity.” The Port Chester Journal, June 5, 1902.[↩]

- “Shell from Maine as Monument.” The New Rochelle Pioneer, June 22, 1912. Untitled article, The Rye Chronicle, June 22, 1912.[↩]

- “Port Chester’s Celebration.” The Rye Chronicle, July 6, 1912.[↩][↩]

- “Port Chester Cash Bargain House.” The Port Chester Journal, October 15, 1896.[↩]

- “Another Maine Relic.” The Rye Chronicle, June 21, 1913.[↩]

- “Local Man Weds a Sister of Maine Hero.” The Daily Argus, Mount Vernon, N.Y., February 25, 1914.[↩]

- “Veterans Of ’98 To Honor Foreign Hero On Battleship Maine.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., February 13, 1930.[↩]

- “Maj. Darcey, 90, Dies; Spanish War Veteran.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., October 31, 1966. William A. Darcey card, New York Abstracts of World War I Military Service, Ancestry.com.[↩]

- “Memorial Favored By Park Board.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., July 13, 1935.[↩]

- “Port Chester’s Soldiers’ Monument.” The New-York Tribune, August 12, 1900.[↩]

- “Criticism Of Illava Model Recalls 40-Year-Old Dispute Over Civil War Memorial.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., August 7, 1936.[↩]

- “Memorial Favored By Park Board.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., July 13, 1935.[↩]

- “War Memorial Project Wins WPA Approval.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., March 4, 1936. “War Memorial Cost To Village Is Only $1,500.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., March 5, 1936.[↩]

- “Launch Work And Memorial On Playground.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., March 10, 1936. “Cutters Scarce, Statue Project Off Schedule.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., August 27, 1936.[↩]

- “Eleven Feet of Clay in Art Tempest.” The Literary Digest, August 15, 1936 (Volume 122, Number 7).[↩]

- “A Doughboy Sculptor Portrays His Comrades.” The New-York Tribune, July 13, 1919.[↩][↩][↩]

- “Karl Illava, Sculptor and Teacher, Dies.” The New York Herald Tribune, May 17, 1954.[↩]

- “Col. Roosevelt as an Art Critic Attacks Awards Made by Judges.” The Washington Post, December 3, 1915.[↩]

- Karl I. Morningstar card, New York, Mexican Punitive Campaign Muster Rolls for National Guard, 1916-1917, Ancestry.com.[↩]

- “Memorial to 27th and 30th Division.” The New York Times, March 14, 1920.[↩]

- “Sculptor Weds Miss Brown; Marriage Takes Place at All Souls’ Church Here.” The New-York Tribune, January 11, 1920.[↩]

- “Art Notes at Home and Abroad.” The New York Times, 1 July 1923.[↩][↩]

- Westchester County Land Records Liber 2607, 160-161.[↩]

- Leo Friedlander Studio National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form.[↩]

- “Harmon Awards Contest Closes on September 10th.” The New York Amsterdam News, September 5, 1928. “3 Negroes Get Harmon 1929 Prizes for Art.” The New York Herald Tribune, January 5, 1930.[↩]

- “Well Known Sculptor Opens Studio to Scarsdale Group.” The Scarsdale Inquirer, October 17, 1930.[↩]

- “To Conduct Course.” The Herald Statesman, Yonkers, N.Y., September 27, 1934. “Large Student Group Departing For College From White Plains.” The New York Herald Tribune, September 20, 1931. ”Westchester Art Exhibit Opens.” The New York Times, May 16, 1933.[↩]

- “107th Infantry Memorial Model Put on Exhibition.” The New York Herald Tribune, January 18, 1927.[↩]

- “Bronze Arrives To Honor Dead Of 7th Regiment.” The New York Herald Tribune, September 14, 1927.[↩]

- Westchester County Land Records Liber 3157, 339-343. “The Village Vagabond.” The Bronxville Press, March 22, 1932. “To Open Art School in Bronxville.” The Bronxville Review, October 15, 1932.[↩]

- “Illava’s Model Faces Danger of Crumbling As Officials Wait Further WPA Action.” The Daily Item, Mount Vernon, N.Y., August 1, 1936.[↩]

- “Work of Art Stirs Port Chester Row.” The New York Times, July 24, 1936.[↩][↩][↩]

- “Memorial Statue A Heated Subject.” The Bronxville Press, July 30, 1936.[↩][↩]

- “Village Officials Divided In Opinion As War Statue Draws Confusing Views.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., July 27, 1936. “Memorial Statue A Heated Subject.” The Bronxville Press, July 30, 1936. “Spanish American War: Rhode Island Veterans” sos.ri.gov/archon/?p=digitallibrary/getfile&id=154[↩]

- “WPA Critics Reject War Statue.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., July 20, 1936.[↩]

- “Village Officials Divided In Opinion As War Statue Draws Confusing Views.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., July 27, 1936.[↩]

- “Grotesque War Statue Stirs Storm Of Debate.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., July 23, 1936.[↩]

- “Grotesque War Statue Stirs Storm Of Debate.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., July 23, 1936.[↩]

- “Opinions Vary As Trustees Prepare To Inspect Statue.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., July 25, 1936.[↩][↩]

- “Illava’s Model Faces Danger of Crumbling As Officials Wait Further WPA Action.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., August 1, 1936.[↩]

- “Village Officials Divided In Opinion As War Statue Draws Confusing Views.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., July 27, 1936. “Memorial Statue A Heated Subject.” The Bronxville Press, July 30, 1936.[↩]

- “Diehl Thinks State Would Shock Public.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., July 31, 1936.[↩]

- “Village Officials Divided In Opinion As War Statue Draws Confusing Views.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., July 27, 1936. “Dr. McKim, Veteran of 2 Wars, Resumes Battle On Insects.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., August 15, 1946.[↩]

- Ibid. “Obituaries.” The Review Press-Reporter, Bronxville, N.Y., April 16, 1998.[↩]

- “Our Own Idea.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., July 27, 1936.[↩]

- “Chamber Members Turn Thumbs Down On Statue.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., July 29, 1936.[↩]

- “WPA Critics Reject War Statue.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., July 20, 1936.[↩]

- “Critics Reject War Memorial At Port Chester.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., July 30, 1936.[↩]

- “Port Chester Art Rejected By WPA.” The New York Times, July 30, 1936.[↩]

- “Illava Assails WPA Critics.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., July 31, 1936. “Critics Reject War Memorial At Port Chester.” The New York Herald Tribune, July 30, 1936.[↩]

- “Statue Rejected; Sculptor Flays WPA Art Officials.” The Bronxville Press, August 6, 1936.[↩]

- “Village To Select New War Memorial.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., August 4, 1936. “Illava’s Model Falls Apart, Thus Solving WPA Problem.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., August 12, 1936. “Is W.P.A. Statue Art? Drought Ends Duispute.” The New York Herald Tribune, August 13, 1936.[↩]

- “Cutters Scarce, Statue Project Off Schedule.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., August 27, 1936.[↩]

- “Illava Designs Statue Despite WPA Snub.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., August 29, 1936.[↩]

- “Illava Will Not Re-enter Port Chester Art Rivalry.” The New York Herald Tribune, September 6, 1936.[↩]

- “Statue Committee Refuses To Make Choice as WPA Submits 2 Instead of 6 Models.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., 13 November 1936.[↩][↩]

- “WPA Rejects Appeal to Reinstate Illava.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., December 10, 1936.[↩]

- “WPA Art For Statue Again Fails.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., February 9, 1937.[↩]

- “Board Accepts New Illava Model For War Memorial.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., April 20, 1937.[↩]

- “Village Takes Illava’s Model and He Smiles.” The New York Herald Tribune, April 20, 1937.[↩]

- “Statue’s Here But Won’t Be Dedicated ‘Til Memorial Day.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., November 10, 1937.[↩][↩]

- “Bronze Statue For Memorial To Cost $2,500.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., July 7, 1937. “Spanish War Statue Ready, Due to Be Erected Saturday.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., November 2, 1937. “Bond Issue for Statue.” The New York Times, July 11, 1937.[↩]

- “Statue’s Here But Won’t Be Dedicated ‘Til Memorial Day.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., November 10, 1937.[↩]

- “Smyth Advises Preparedness As Memorials Are Dedicated.” The Daily Item, 25 April 1938.[↩]

- “Obituary: Karl Illava.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., May 17, 1954. “Art Takes a Holiday to Brew Sea Stew.” The New York Evening Post, September 22, 1943.[↩]

- Westchester County Land Records Liber 3417, 411-413. Leo Friedlander Studio National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form.[↩]

- “Obituary: Miss Frances Rising.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., March 25, 1944.[↩]

- United Spanish War Veterans. Department of New York. Proceedings…for the year 1955 (New York: Herald Square Press, Inc., 1956), 96.[↩]

- “Maj. Darcey, 90, Dies; Spanish War Veteran.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., October 31, 1966. “Obituaries: Walter F. Praray.” The Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., April 6, 1970.[↩]